ROSE HILL — In the early 1970s, a young freelance writer named Reed Wolcott arrived in Rose Hill. A graduate of a small college in Vermont and originally from upstate New York, she had secured an assignment with the New York Times to write a story about a small southern town during a time when the country was experiencing significant turmoil, including race riots and the Vietnam War. Unbeknownst to the townspeople, her visit would lead to a book that would be talked about in Rose Hill for years to come—though not with fondness.

In typical small-town fashion, word spread quickly that a writer was in town to write a story about Rose Hill. That created some excitement among the residents.

“I was a young fellow whenever she came to town,” Rose Hill Mayor Davy Buckner said in an interview with Duplin Journal. “Everybody knew (she was in town) and they were waiting for her to interview them. She made her rounds.”

Buckner said she frequently ate in his restaurant.

Wolcott ended up staying in Rose Hill for about two years, at first checking into the Rose Hill Motel before moving into a home with a rough reputation in town.

“She stayed in an old house across the street (from the current town hall),” Rose Hill native Bobby Ward told Duplin Journal.

Buckner acknowledged the household’s reputation at the time, saying locals considered it one of the more troubled homes in town.

Ward said Wolcott interviewed both him and his father, Robert Ward. While parts of his father’s interview appear in the book, his interview with her did not because he would not sign a release after the interview.

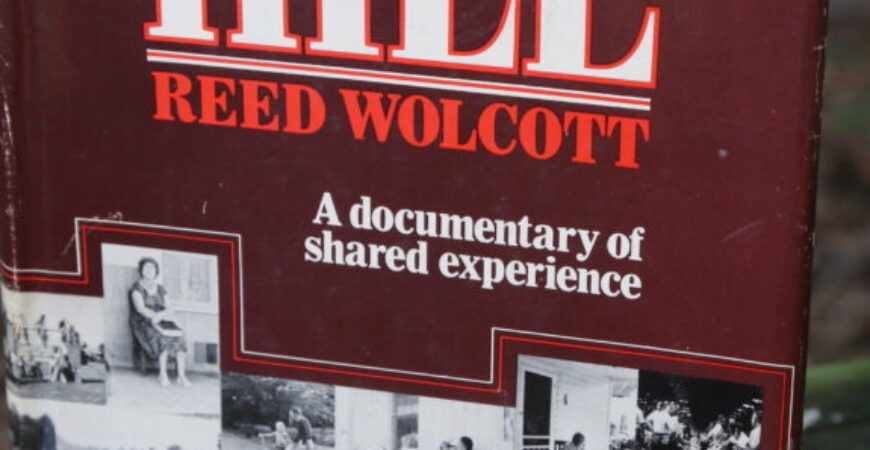

Expecting a story in the New York Times about Rose Hill, the town was surprised when word made its way quickly through the area that a book had been released in 1976 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, a New York publishing house. There was no doubt what, or who, the book was about. The title was Rose Hill.

“I do know everybody around here got a copy,” Buckner said.

In the book, Wolcott used the names of real people in some cases and used fictitious names in other interviews. Buckner said it was those fictitious names that attracted attention locally.

“We read it to see if we could figure out who the chapter was about,” he said.

Buckner admits some of the stories appearing in the book are “kind of funny,” and there were some moving stories about some of the young men who went to serve in Vietnam. However, with a few exceptions, most Rose Hill residents were disgusted with the overall tone of the book that bore their town’s name.

“It was very negative because it put a black eye on Rose Hill,” Ward said. “She came to a small southern town to degrade it. She did it to sell a book.”

Buckner was equally unimpressed.

“In my opinion, it was basically somebody coming to write a book about the trash in Rose Hill, about a little Peyton Place, who was ‘doing who’ and that sort of thing,” Buckner said.

Buckner said he recalled one particular interview in the book with a lady in which Wolcott used her real name.

“She was known for always criticizing the area,” Buckner said. “She always talked bad about our schools. She even talked about how the schools didn’t have enough money to put (feminine products) in the girls’ bathroom.”

“She wanted to look at the bad,” Ward said of Wolcott. “She didn’t want to look at the good.”

Not all memories of Wolcott’s time in Rose Hill are void of any humor. Former mayor Sue Lynn Bowden, whose parents opened the Rose Hill Motel, recalled a time she walked into the motel office to find her mother at the switchboard with the headset to her ear.

“I tried to talk to mom and she held up her hand for me to hush, to be quiet,” Bowden said. “Later, she told me she was listening in on a call Reed was making.”

After the release of the book, Reed Wolcott was never seen in Rose Hill again. A few people in town echoed the same sentiment, that it was likely in her best interest not to come back to town.

While the book never became a bestseller, it was reviewed by several nationally recognized newspapers, including the New York Times. Nearly 50 years later, copies of the book are hard to find, but the wounds it left behind are still apparent.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram