Largemouth bass downstream of Lear Corp in Kenansville contains PFAS levels 20 times higher than fish deemed unsafe to consume by the state

KENANSVILLE — Concerns about PFAS, also known as forever chemicals, have plagued residents of numerous communities along the Cape Fear River, and most recently, heads have turned to Lear Corporation, an industrial textile facility near Kenansville that discharges treated domestic and industrial wastewater to the Northeast Cape Fear River.

In April, Duplin Journal wrote a story about a draft permit that, if approved, would allow Lear to legally discharge PFAS into the river after a violation landed them in hot water and a requirement to report the discharges. Since then, residents like Jessica Thomas, who lives only a couple of miles downstream from Lear, have become aware of the contamination and sought help from local and state officials to protect the communities exposed to these dangerous chemicals.

Thomas appeared before the Duplin County Board of Commissioners in August, hoping to find solutions. “Their stance was we’re not a regulatory agency, but I wasn’t asking them to regulate Lear. I was asking them to speak up in an official capacity on behalf of their community,” Thomas told Duplin Journal, adding that she also reached out to Kemp Burdette, the riverkeeper who discovered the illegal PFAS discharges.

“I went out and I tested fish,” said Cape Fear River Watch’s Burdette. “I caught fish in the Northeast Cape River downstream of the Lear facility near Sarecta. I was about five miles downstream of the discharge at the Lear facility.”

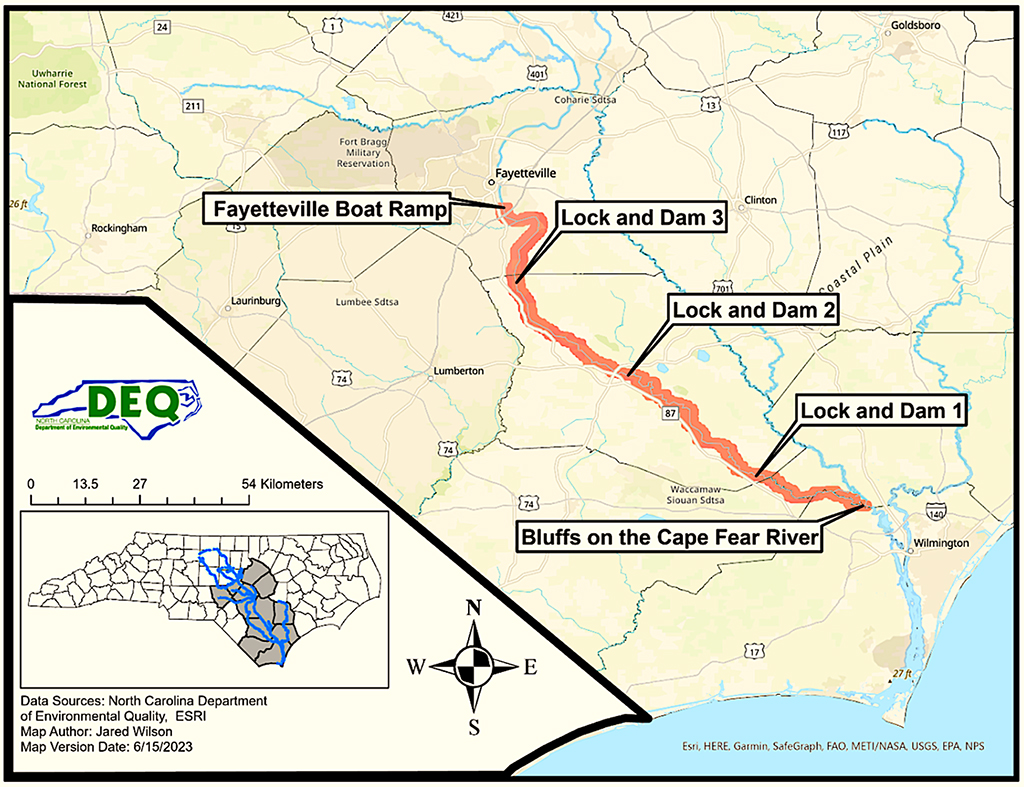

Burdette told Duplin Journal that he submitted the fish samples to Gel Laboratories — the same lab the state used to test fish from a section of the Cape Fear from Fayetteville to the mouth of the Black River that led to a fish consumption advisory about a year and a half ago.

The lab results revealed the largemouth bass downstream of the Lear facility contained PFAS levels that were 20 times higher than those found in fish from the Cape Fear River downstream of Fayetteville. What is most concerning is that people in Duplin County are fishing and going about their lives, completely unaware of this. The advisory issued on July 13, 2023, for the middle and lower Cape Fear River, stated that children, women of childbearing age, pregnant or nursing, should avoid eating largemouth bass, bluegill, flathead catfish, striped bass, and redear altogether. And the rest of the population should not consume more than one bluegill, flathead catfish, largemouth bass, striped bass, or redear per year combined across all species.

“The small bluegills were 12 times higher, and the large bluegills were eight times higher. So the fish in the Northeast Cape River downstream of Lear have way more of this toxic pollutant in their flesh than the fish in the Cape Fear that we’ve all been focused on because Chemours got a lot of focus because it was a large emitter of PFAS above the drinking water source. But it turns out that Lear is actually worse — A lot worse, 20 times worse,” Burdette told Duplin Journal. “We know that people eat those fish. You can go to the bridge at Sarecta, and you can walk out on that bridge, and you can look in the trees on either side of the bridge, and you can see all of the fishing lures that are stuck in the trees where people have been trying to catch fish … That’s always a clear indication that people are fishing there.”

Burdette shared that they reported it to DEQ, urging them not to issue a permit that allows Lear to continue discharging PFAS.

PFAS are multi-organ toxicants associated with altered immune and thyroid function, liver disease, lipid and insulin dysregulation, kidney disease, adverse reproductive and developmental outcomes, and cancers. According to the EPA, they can accumulate in individuals who are exposed to them over extended periods. There is no known way to get them out of our bodies except for giving birth and breastfeeding, resulting in mothers offloading it into their newborn babies, unleashing a chain of health problems with implications for future generations to come.

“If we know that PFAS are dangerous, toxic pollutants that have clear links to a variety of cancers and other health conditions, and a company says we’re not going to discharge it, then why would we issue them a permit to discharge it?,” said Burdette. “The company itself has said that they are going to phase out PFAS. … Yet the state is about to issue them a permit that would allow them to discharge PFAS for the next five years.”

Burdette emphasized that the new permit will allow Lear to discharge PFAS “and what that says is that the company and the state think it’s more important for this company to save money on waste treatment technology than it is to protect human health and the environment.”

While the draft includes a compliance schedule with requirements to conduct studies to analyze PFAS, technology, and management practices to control PFAS, there is a growing concern that with each passing day, more toxic chemicals continue to be discharged into the waters Duplin residents use for fishing and recreation.

“Every day they spend studying is another day that stuff goes into those fish. They can study it for years,” said Burdette, adding that the technology to remove PFAS is well understood and used across the state.

“They have chosen not to do that in the past because it costs money, so it means that they felt like their profits were more important than putting this toxic chemical into the river and letting it go downstream and contaminate fish,” said Burdette.

For the past several months, Thomas has been asking for a new public comment session.

Last week, DEQ announced Tuesday, Dec. 17, as the date to hear public comment on the proposed renewal of the national pollutant discharge elimination system permit for Lear Corp. The session starts at 6 p.m. at James Sprunt Community College Monk Auditorium.

“We need the landowners and the people that use the river to fish and recreate to show up and say, hey, this is our backyard. These are our lives, and we don’t want you playing with it anymore,” Thomas told Duplin Journal.

“My family’s property is at the last part of the navigable waters for the Northeast Cape Fear River, you cannot get much further than my backyard on a boat, but the river is a big fishing spot for a lot of people,” said Thomas. “We need to make sure that people know about this issue and that they are involved … one person speaking up, yes, of course, it makes a difference, but when you have everyone speaking up in unison, that’s when we’re heard.”

Thomas has three sons, aged 8, 10, and 12, who have been playing in the river their entire lives. She recounted that she first noticed the foam in 2018 when she and her husband were on a boat passing the Lear discharge site.

“We just assumed that because they are permitted by the state that everything was fine,” said Thomas.

“I wrote emails to Jimmy Dixon, Brent Jackson, all of the county commissioners, Greg Murphy, just about everybody under Kamala Harris trying to get help here,” said Thomas, adding that in the past couple of months, she has reported them to DEQ twice for visible foam on the river, “which is a violation of their permit,” said Thomas. “Lear says that they are phasing this out… our concern is what are they putting in place of this stuff?”

Thomas noted that Lear Corp is a large taxpayer in Duplin County and provides a lot of jobs.

“I think that’s probably another reason people are being quiet about this,” she said. “But the people that work out there need to be asking, what chemicals are we around? What have y’all been exposing us to?”

Burdette noted that river contamination can easily seep into well water during flooding, posing a significant health risk. He explained that the interaction between groundwater and surface water is common, requiring ongoing monitoring. Groundwater can both feed rivers and receive water from them, depending on the flow conditions. In low-flow periods, water typically moves from aquifers to rivers, while during high flow, contaminated river water can enter aquifers. He emphasized that during significant floods, such as those caused by hurricanes, contaminated river water can infiltrate wells, leading to well contamination.

Editors Note: In addition to the public comment hearing on Dec. 17. The public can mail their comments to Fenton Brown Jr., NPDES Wastewater Permitting, Attn: Lear Corporation Permit, 1617 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, N.C., 27699-1617. Letters must be postmarked no later than Dec. 18.

Public comments may also be submitted by email to: publiccomments@deq.nc.gov. Please include “Lear Corporation Permit” in the email subject line.

The draft permit and a technical fact sheet can be found online.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram